Myth-Busting of the Perfect College Applicant

What does a strong application for college take? Perfect stats, several diverse extracurriculars, the right subject combination, among a jumble of other boxes to be ticked, and you’re good to go… right? I wouldn’t put all my money on that just yet. I’m writing today to debunk the idea that there is a prescribed set of boxes that you can check to make yourself the “right” applicant for a certain college, or at the very least that it is the only reliable, tried and tested way. I will also discuss some fairly ordinary strategies were key to my own admissions in the US, specifically highlighting your own unique strengths and passions in your application. Here we go!

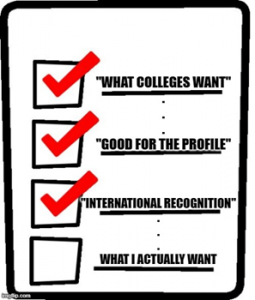

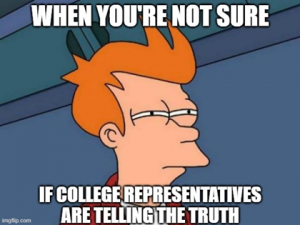

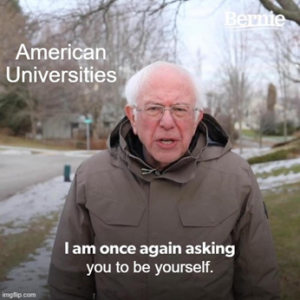

There is a glaring inconsistency when it comes to the strategy of ticking boxes to make yourself the right candidate: if colleges were indeed looking for a specific archetype of student to admit, most, if not all their students would be quite similar—overachievers in about a dozen different fields. From personal experience, I know that this isn’t the case. At Harvard, I’ve met a body of students as diverse as they come. Some are keen to research, others to perform, and others still to code. Each of them is unmistakably passionate, talented, and qualified for their own pursuit. Yet I haven’t seen any one person with high achievements or proficiency in more than two or three areas of interest. Back in Delhi, I have known people to go out of their way to obtain a prestigious international certificate or conduct research largely irrelevant to their actual interests, all in a bid to ace college admissions. I remember the time when college representatives came to my school, hounded by questions about extracurriculars and testing, to which their uniform response was that we should take up things that interest us. One of them pointed out that a chemistry SAT Subject Test for an application largely founded on the humanities could seem out of place, rather than indicating versatility, and wasn’t something that colleges necessarily looked for. All I did, and I urge you to do, is take these people at their word.

Rather than moulding oneself into the “ideal” candidate, using your own strengths to build a profile and make a successful application has two principal advantages. Firstly, exploring areas that are of interest to you can give you interesting experiences and unique insights to share in the written part of your application, things that those without a sincere passion might not notice. A cricketer can critique in-depth the strategy employed by a team in the World Cup or an aspiring mathematician can speak about a topic of particular interest to them, for example—things that cannot be done without having an innate understanding of your chosen field. Secondly, this leads to a more rewarding application process. What would you rather do, commit long hours to tasks that you don’t really care about, or spend endless hours doing what truly excites you? I’m aware that knowing one’s own passions isn’t always easy, but I promise you that identifying them is a task worth your time.

Even the less tangible qualities of a person can be an important consideration in admissions. An article by a former admissions director at Brown that I read spoke about how kindness is a quality that shone brightly in applications and one that they particularly regarded, even though it had no fixed indicators. The majority and highest of my achievements were the ones for which I had no certificates or trophies to show. Yet they were so crucially formative that they still impact the way I do things. Those were the ones I spoke about most in my applications, because they were what I cared most about. There is merit in surprising the admissions officers with whom you are, rather than giving them what you think they expect. The bottom line is that American universities will respect you more for seeking things of value to you than for seeking those supposedly more valuable to them, something that is apparent in how the application process is structured.